Notes on Sequentially Constructive Concurrency

- Published on

Bilbliography

Von Hanxleden, Reinhard, et al. Sequentially Constructive Concurrency a Conservative Extension of the Synchronous Model of Computation. 2013.

tl;dr

An extension to the synchronous model of computation that is less restrictive on what programs are considered valid, yet still preserves deterministic concurrency.

Context

The synchronous languages Esterel etc were created in the late 1980s, Java was created mid 90s. Different threading/concurrency models have been explored due to the limitations of the different models currently in play.

What

This paper proposes the Sequentially Constructive Model of Computation (SC MoC). The SC MoC is an extension of the synchronous MoC that allows more flexible variable access by analysing the control flow to prevent race conditions.

Why

The original synchronous languages use a static scheduling technique which ensures variables only have a single value per tick by ensuring a) writes occur before reads b) each variable only gets written once per tick This does provide determinism, but this paper argues it's not necessary and limits expressiveness by forbidding natural looking sequential code such as:

if (!done) {

done = true

}(this code violates the rule that writes occur before reads)

Related Work

- Edwards and Potop-Butucaru's work on compilation challenges for concurrent languages.

- Esterel's deterministic concurrency model.

- Caspi et al.'s extensions to Lustre with shared memory models.

- The development of Synchronous C and PRET-C for deterministic concurrency.

- SHIM's approach to concurrent Kahn process networks.

- Various approaches to scheduling in Statecharts by Pnueli and Shalev, Boussinot, and Berry and Shiple.

How

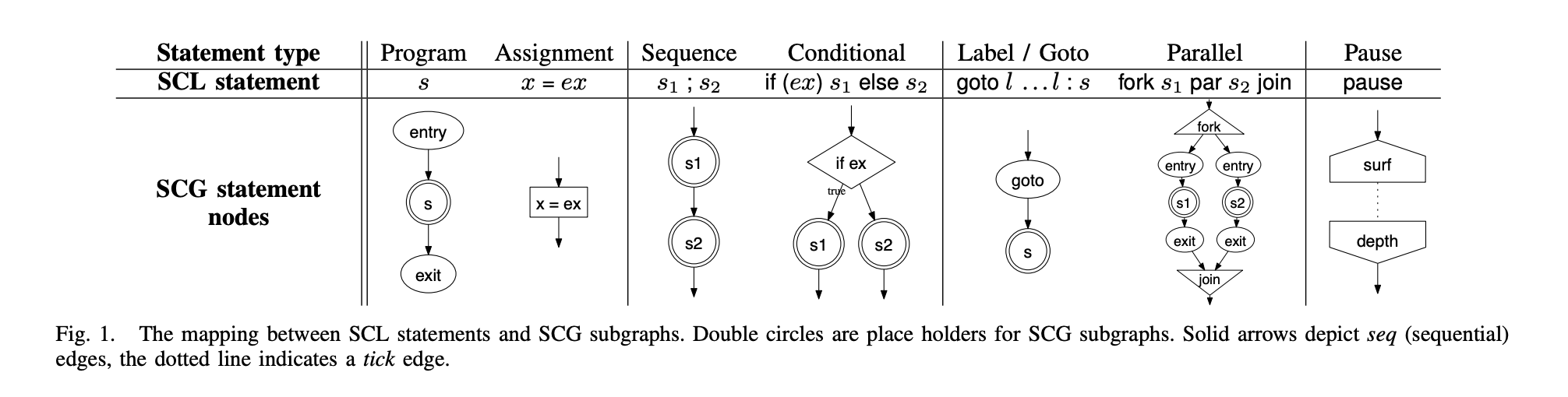

A small SC language (SCL) is created to demonstrate the SC MoC (it could apply to many languages). An SC Graph (SCG) is an internal representation of the concurrent and sequential control flow, used for analysis and code generation.  The three types of violations in the Sequentially Constructive Model of Computation (SC MoC) are:

The three types of violations in the Sequentially Constructive Model of Computation (SC MoC) are:

- Non-confluent Writes Violation: This occurs when two operations write to the same variable in a way that the result depends on the order of the writes. Since this order isn't guaranteed in concurrent programming, it leads to unpredictable outcomes.

- Read-After-Write Violation: This happens when a variable is read and then written to in the same tick by different operations. The read operation might not get the latest value, leading to inconsistencies.

- Relative-After-Absolute Write Violation: This is when a variable is first written to in an absolute manner (direct assignment) and then written to again in a relative manner (using a combination function) within the same tick. This can disrupt the intended sequential constructiveness of the program.

These rules are summarised as:

within all ticks t, for all variables v that are accessed concurrently within t, “any identical absolute writes on v before any confluent relative writes on v before any reads on v.”

Analysis Sequential Constructiveness

In the Sequentially Constructive Graph (SCG), the node relations determine how operations can occur without creating cycles that would disrupt the program's determinism:

n1 ↔ww n2: Indicates non-confluent writes to the same variable by nodesn1andn2. If such a relation exists, it could create cycles, violating acyclic properties.n1 →wir n2: Represents any write, increment, or read dependency betweenn1andn2. A cycle containing these edges could lead to read-after-write conflicts or other scheduling issues.

For a program to be acyclic SC schedulable, it must have no n1 ↔ww n2 relations (avoiding non-confluent write conflicts) and no cycles containing →wir edges (ensuring orderly access to variables without conflicts).

For a sequentially constructive program, a valid schedule is one which executes concurrent statements in the order induced by →. Such a schedule may be implemented by associating a priority

n.prwith each statement node n.

"The priority

n.prof a statement n is the maximal number of →wir edges traversed by any path originating in n in the SCG."

The calculation of priorities can be formulated as a longest weighted path problem

Notable References

Milners Synchronous Product

The basic construct that all these (synchronous) languages provide, is a notion of synchronous concurrency, inspired by Milner's synchronous product

R. Milner. On relating synchrony and asynchrony. Technical Report CSR- 75-80, Computer Science Dept., Edimburgh Univ., 1981.

R. Milner. Calculi for synchrony and asynchrony. TCS, 25(3), July 1983.

The Synchronous Languages Twelve Years Later

A. Benveniste, P. Caspi, S. A. Edwards, N. Halbwachs, P. L. Guernic, and R. de Simone, “The Synchronous Languages Twelve Years Later,” in Proceedings of the IEEE, Special Issue on Embedded Systems, vol. 91, Jan. 2003

SyncCharts

R. von Hanxleden, “SyncCharts in C—A Proposal for Light-Weight, Deterministic Concurrency,” in Proceedings of the International Confer- ence on Embedded Software (EMSOFT’09). Grenoble, France: ACM, Oct. 2009, pp. 225–234

Notable Quotes

The execution of Control begins with a fork that spawns off Request and Dispatch. These two threads then progress on their own. Were they Java threads, a scheduler of some run time system could now switch back and forth between them arbitrarily, until both of them had finished. Under the SC MoC, their progression and the context switches between them are disciplined by a scheduling regime that prohibits race conditions. Determinism in Control is achieved by demanding that in any pair of concurrent write/read accesses to a shared variable, the write must be scheduled before the read. (pg 2)

Only the output values emitted at the end of each macro tick are visible to the outside world. The internal progression of variable values within a tick, i. e., while performing a sequence of micro ticks (cf. Sec. III-C), is not externally observable. Hence, when reasoning about deterministic behavior, we only consider the outputs emitted at the end of each macro tick. (pg 2)